Technecropolis Archaeology, Part I: The Technological Necropolis

The computer is dead. Long live the flesh.

This is one of those posts that I typed up in an effort to realize the idea I have in mind… It is disorganized, and highly exploratory. I continue to try to understand this idea under the “Technecropolis Archaeology” series, as the concept includes many disparate fields of study, and requires hours of dedicated research to make deeper connections and validate my intuitions. [this note was made on 24 february 2025]

What began as an entry into the “Why I Hate Art” category of armchair cultural critique—as a hysterical female thinker, who so arrogantly dispels my feeble-general-public-masturbatory-anthropological-fantasies-of-awareness-knowledge-and-sentience-fetishism onto the digital world—I came to realize just how deeply I loathe imagery. Imagery is idolized in art, but it is not restrained to that criminal, white-collar, money laundering, image-industry. The entire social world is an image-machine. However, my iconophobia isn’t novel or new, making research into exactly why I hate art an overwhelmingly broad inspection into the bowels of history. I can’t simply point to Instagram and explain why I dislike art, when the aversion to images is one of the earliest taboos ever recorded (see Exodus 20:4).

There were always faint glimmers of this personal hatred, going back to my paranoia over the shape of letters and language itself—anxiety about the way my mouth moves when I speak, how words form it, how words take control of the muscles in my jaw and cheeks; the way ears look like funnels, exposed and draining airwaves; how faces are sculpted by the vibrations they receive (I can conduct free plastic surgery on you by screaming into your face for 90 days straight). Specifically, the letter I conjures in me, a great deal of fear, distrust and anxiety, particularly, because, if repeated enough, “I” literally becomes prison bars (the image of which is the origin of this newsletter’s icon). Consider the psychic restraints created by how much typing, literature and writing begins with I, I, I. First person, singular: I, I, I. Consider English as the lingua franca of the internet. Consider: IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII.

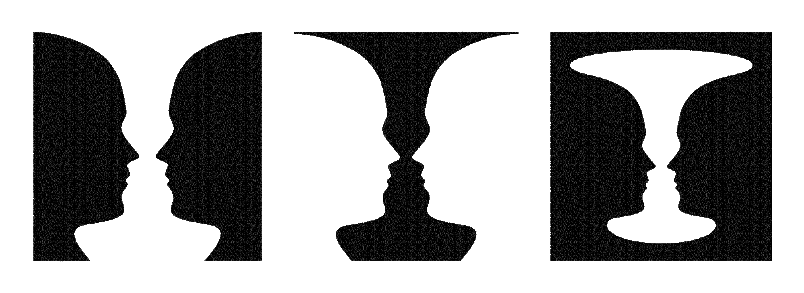

The creation of “I,” from a line drawn in the sand, the sign of division and separation — a line, like “I,” presents an automatic duality — a boxing in and a closing out. It is the representation of a duality sensed between bodies in a tribe, tribes on a planet, stars in space: I, alone, and the rest of this. “I,” also, maybe obviously, creates an individual. Just look at the word individual — the etymology of the word, and its appearance: in, div, dual:

<in>dual</in>The individual is contained within the dual division, inseparable from the larger “in.” “I” creates a dual opposition: I, and everything outside (many people forget: the outside always remains within). “I” is a war zone, haunted by the empires fallen in the fight to spell ich, to define what, and who, an “I” is. Who gets the privilege to be a singular, capitalized entity? “I” is wrought with the rules inherited from the past, all the I’s and former its that came before it; the blood shed to bring “I” into its current existence, to keep it there, to democratize it. Socially mediated, and dependent on language, “I” keeps us confined inside of it. “I” is the beginning of image, literally and figuratively. From “I” comes the frame, the right angle. The line provides definition.

We are confined and atomized by “I”: its angles, lines, and bars. The more we use it, the more it binds us; the narrower our confines become. The letter “I,” and its recursive duplicate—the individual—allow so much space between interactions that entire industries crop up to fill the space of mediation. Once intervened only by the air between a face-to-face encounter, we are now sheathed in the petroleum-based condoms of screens, phones, and plastic barriers left over from pandemic protections. We are mediated and controlled by means. You are not you. You are definitely not I. You are a cashier, a wife, an entrepreneur, a financial slave. “You” is the hidden, secret face of “I”; the diminutive, weak, and effeminate opposite to the capital, singular, omniscient, all-seeing “I.” Once “I” comes to dominate, you cease to exist.

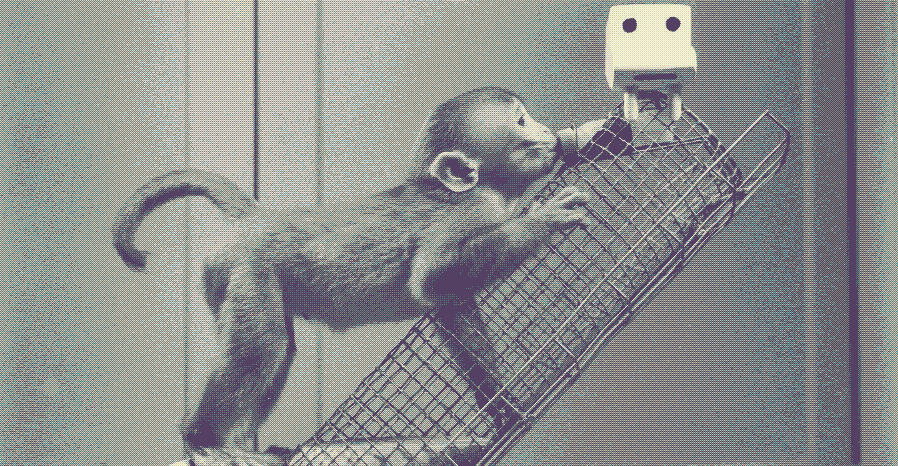

Maybe there are still ways to experience connection though presence and authenticity—by way of magnificent, divine enchantment of all things; intensely terrific humanization, as opposed to the cold and cruel dehumanization of “I” and “it”. The authentic experiencing of you, as you who creates me, and you and i become we, bound together, is most notably explored in Martin Buber’s I and Thou, among others (Levinas, Merleau-Ponty, Plotinus, who tried to move beyond the mirror and transcend the very imitativeness that makes us apes).

The “I” is so many things, but for our purposes, it is everything: cycloptic, panoptic, prison and warden, authoritarian, tyrant, victim, and executioner.

Consider the “I” when imagining how children must feel, growing up with iPhone cameras pointed at them from the moment they are born. Only the camera remains constant—the living bodies behind the apparatus are interchangeable, deindividuated. The screen is forever, flesh decays, and the eternal “I” remains at the center, perpetually gazing, watching, recording.

However, there is absolutely no way you are human to me—or to anyone else—through a screen. There is no way you are human when reduced to a data point, a representation of some quality, a behavior—fixed and crucified as a static “thing.” You cannot be both human and a number, ranked in a consumer demographic pile. You cannot be both human and a rendered, platonic ideal of a universalized human being.

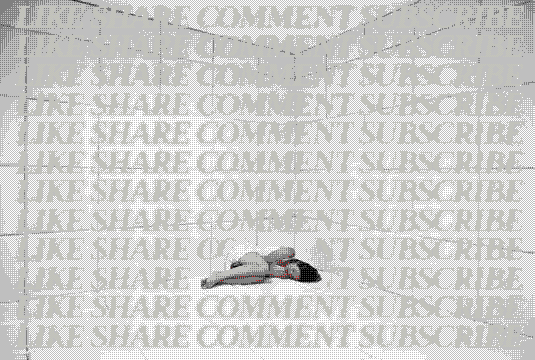

“You” do not exist—there is only me, money, and machinery. Me, and my freedom. Me, and whatever I choose to see as mine. There is no you—only your quantified, calculated actions, which I provide to you. You can only do as I command: like, share, subscribe, comment. This is the future I want for you.

Neither you nor I have ever—or will ever—appear in materiality. We are each confined to our minds and bodies, limited by the way we calculate and categorize each other’s actions and appearances. Yet, there is no actual distinction between you and I. We are interchangeable—every “I” is also you, and there can be no “I” without “you.” In reality, there is only we: the human hive, the terrestrial biosphere, the sum of humanity’s actions. The One World Government has existed since the wetness of Earth’s water.

There is no genuine substance behind “I.” It is useful, of course, for communication and second-order understanding—to give material bodies signification. Yet, within its shadow, this very superficiality and abstraction of the you-I duality enables the totalizing domination and exploitation of imagination. “I” is both the bridge to connection and the blade’s edge of amputation.

The dual use of “I” opens up the possibility for a uniquely insular selfishness—one in which many of us currently inhabit. The millions of competing I’s enforce and coerce other individuals into maintaining and legitimizing the evisceration of a possible you. The “other” is not a threat, but a nuisance, a pest, an inconvenience to the supreme agency of the all-consuming, totalitarian “I”—a singular body that increasingly demands its subjects to be streamlined, economized, perfected, and optimized.

Intentionally or not, technologically informed neoteny, arrested development, collective trauma, advertising, and psychological operations all work to magnify the “I” and drive the self away from others: out of fear, anxiety, exhaustion, insecurity, scarcity, and intolerance. The “I” becomes incapable of encountering an equal—yet, at the same time, totally dependent on others to define itself. If you cease to exist, so do I. Yet, we are confronted with a stark contradiction since we remain perceptually and physically separate as bodies, yet socially reliant on one another to define ourselves as individuals. The necessity with which individuals need one another fosters a real kind of resentment, especially in the face of failures to achieve the deeply human, face-to-face, almost spiritual encounters required to develop a functional self and individuality. This isolation is both mundane and global, reinforced by everyday actions (calling to schedule an appointment, buying groceries, driving), domestic and social performances (as student, employee, friend), and the domain of service production and consumption (posting content, buying things, becoming skilled).

As the I’s of the world continue to shrink behind screens, hide behind counters, and burn out in exhausting jobs—fearful and threatened by strangers, aliens, and outsiders; scanning their home surveillance cameras, keeping their kids away from others, financializing friendships, and creating content from every possible interaction—the “I” grows insecure and narcissistic, denied any other who can define it, denied any living experienced of intersubjectivity. A libertarian ethos reverberates in the individual: “I” comes to regard the external as an audience, a population, a resource. It is sovereign against the chaotic unknown—and it doesn’t need you anymore. “I” has mirrors, cameras, recordings, and pictures to reflect itself back to itself. What could you possibly offer that it doesn’t already know, that it cannot access by itself, with its machinery? The “I,” initially found in discourse with the world around it, increasingly isolates—locking away in a mute, schizophrenic monologue with the dead material of disciplinary digital wardens and sensory-shaping surveillance apparatuses.

This sterile landscape facilitates endless propagation of self-images, self-mythologizing, and asexual replication—cloning. The “echo chamber” is Narcissus’s water pool, certainly. It is also the Versailles Hall of Mirrors and “the pod”: a digital incubation vat full of surveillance sensors, each one gazing directly at you—wanting, scanning, demanding, and in this confinement, where intersubjectivity is dependent on technology, you learn to desire being controlled by it.

With such a crippled “I”—one that resents how much it needs “you” while simultaneously debilitated by its inability to ever fully encounter “you”—the “I” grows hollow, shifting to distribute itself across externalized images. Its identity depends on how its images are received, since the image is the only part of itself allowed to circulate. The image is the medium through which feedback is received, not the body, not physical action. The world is a discourse of images, marginally puppeted by humans, but mostly by algorithms, software, and Ai agents.

This technological control is the materialization of the death drive—eliminating the need for direct experience, devaluing the imperfections and decay inherent to vitality, smuggling away ugliness and rot, and mutilating people into datasets and spreadsheet-friendly personal information files. Technological control is the desire for stasis and finality.

It would be a mistake to understand image as a mere photograph, performance, visualization, work uniform, or its associated job role. Image is the superficial representation of something—the frame and its contents—even the concept of “I” is an image: an abstract, immaterial framing of something concrete, yet elusive and undefined. This is what language does—it fixes—and wars break out trying to renegotiate and change definitions. Nevertheless, an image is both the exchange between a client and a salesperson, a wedding, a party, a solitary visit to the library—any scene—a moving image—like when you find it romantic to wear a headscarf in a convertible because Audrey Hepburn wore a headscarf in the classic movie Charade (1963). You are the image, and you imitate the image, valuing its framing rather than being left without one. You prefer the simplicity, coherence, and clarity of the image.

Image-based technology externalizes the desire for this domination and control, shaping environments where people exist in a state of suspended animation, endlessly repeating the same interactions without change or consequence.

The difficulty of reconstructing the frames of an image, and the reliance on tools and architectures we’ve inherited—and which are provided to us—only serve to strip-mine the interiority of both you and I. The architecture becomes the embodiment of the self. Gradually, the apparatus that disciplines and guides us becomes endowed with the divine enchantment once assumed to be latent in every human and living thing. The objects gain authority to bestow upon us our lives. Over time, the “I,” in its isolation, becomes an it: nameless, faceless, interchangeable, de-individuated—and the objects begin to take on the subjective “I.” It is the machine, the algorithm, the dataset that decides, applying a newly formulated, opaque logic, determining the final decision: this is what the data says. The objects define our identity and shape meaning—all while reinforcing the very system in which the object was created. It is a sort of possession—a vampiric colonization, an invasion—as the objects become more connected, more animated, we become more isolated and sedentary. As the objects and frames define and calculate more and more organic space, the living world is made inert—docile, as Foucault would put it—biomaterial resources and economic units processed by operations and arranged inside the enclosures devised by digital machinery. The machinery becomes the subject, and life becomes the object.

In effect, the self is projected onto whatever provides a medium for the image. Disembodied, detached, or compartmentalized, the body comes to prefer its glistening, clearly defined image—its reflection—and all the ways in which one can modulate, copy, alter, and replay the image. Life survives at the mercy of—and in service to—the image.

Preferences for ease and convenience are arguably downstream from crude oil production, downstream from domestication, downstream from a galactic alien light wave. Preferences for austerity, control, conformity, and domination continually elevate the image—higher and higher—until the image becomes our absolute ruler. We will be unable—and unwilling—to appeal to another human being who, like you, will be reduced to nothing but a number—a burden on the environment, a burden on the budget. We will appeal to the singular “I”—the I who defines us as we—from inside its lifeless screen, portraying an image of code, the live stream of CCTV security footage, a kill list determined by military intelligence input. Idolization of the image is an idolization of the lifeless.

Billions of I’s who have come before us built the cathedral of a disordered veneration for suffering, sacrifice, and sadism. We inherit that valorization and replicate it from the comfort of our digital stasis: automated killing machines, video games, pornography, legal code, financial transactions, health information—all funneled into software, algorithmic systems—neatly ordered and efficiently calculated.

We enforce this scripture of the dead onto the world of the living, and this ritual is an inversion of the will to survive. Striving to emulate the non-being of images is a rejection of both reality and physical existence. Just as individuality and its incessant I, I, I creates an atomized self-image, so too does the image erect a coffin—enclosed, without reception, no living observer—only endless, infinite, lifeless reflections.

If you look a bit closer, you’ll find that “I,” and all its reflections, are representations of fluctuating states. “I feel sad,” “I like that,” a painting, a visualization—all images are attempts to capture an ephemeral moment of being. The “I” itself is an effort to communicate the private internal state to the public outside. “I” conveys the sense of being alive and presents an opposition to the incommunicable, undifferentiated realm of the dead. “I Am That I Am,” as God once allegedly said (Exodus 3:7-14).

Technological and image-based apparatuses are exercises in controlling the ephemeral mess—organizing time, change, and putting it into a singular, abstract, quantified order. Our preference for this lifeless, clinical predictability and restraint begs the question: from whence does this desire arise?

Is it that our cells drive us toward death, that death is a precondition of life, so we build contraptions to facilitate and ease our descent into oblivion? Is our desire for isolated subjectivity merely an economic byproduct of capitalism and its alien intelligence? Or could it be that Earth, itself, is the territory of a necropolis empire, and our actions here are part of a larger ecosystem—an interface and intersubjective experience—with roots that cross and fold between both realms of the living and the dead?

If you step back far enough, technology isn’t separate from nature—it grows from it. The Technological Necropolis may be the result of capital’s influence on digital systems, but capital itself is just a temporary structure—a parasitic code running on a much older operating system.

The problem isn’t technology. It’s how it’s been captured, shaped, and weaponized to reinforce power structures that were already failing. Capital molds technology into a system of control—monetized surveillance, algorithmic governance, and digital enclosures that trap people in feedback loops.

But if you look at technology beyond the constraints of human economics, it follows a deeper logic:

The internet functions like mycelium—a decentralized neural network growing beyond human intent.

AI mirrors the emergent intelligence of natural systems—from slime molds to planetary weather patterns.

Computation itself is an extension of the universe’s fundamental information-processing nature.

Capital wants technology to be extractive, to be a machine for profit and control. But technology—at its core—is an extension of life’s own evolutionary impulse. When systems collapse, technology will continue to evolve beyond the constraints that capital imposed on it.

The Technological Necropolis is real, but it’s not the final stage. It’s just a bottleneck in a much larger process. The question isn’t whether technology will move forward—it’s whether humanity will break free from capital’s dead logic in time to move forward with it.